Countering Objections

Responses to 12 Potential Objections to Our Developmental Political Approach

- How can you justify your claims that the developmental perspective is “higher” or “more evolved”?

Anyone who wants to make the world a better place must be willing to point in the direction of “better.” Even those who advocate value relativism are, ironically, nevertheless claiming that their interpretation is superior. Developmentalists don’t claim to know what’s better with certainty or finality—we seek to continuously improve our definition of improvement itself. Nor do we claim that the developmental worldview is absolutely better than the worldviews of progressivism, modernism, or traditionalism. We advocate the developmental perspective primarily because it’s more inclusive, because it encompasses a wider range of values, and because it has greater explanatory power than these other value frames.

While the contemporary progressive worldview achieves evolution by better including within its circle of care those who have been victimized or marginalized, the developmental worldview evolves further in the direction of inclusivity by better including modernists and traditionalists within the scope of its political solidarity. Developmentalists thus seek to include not only those who look differently, but also those who think differently.

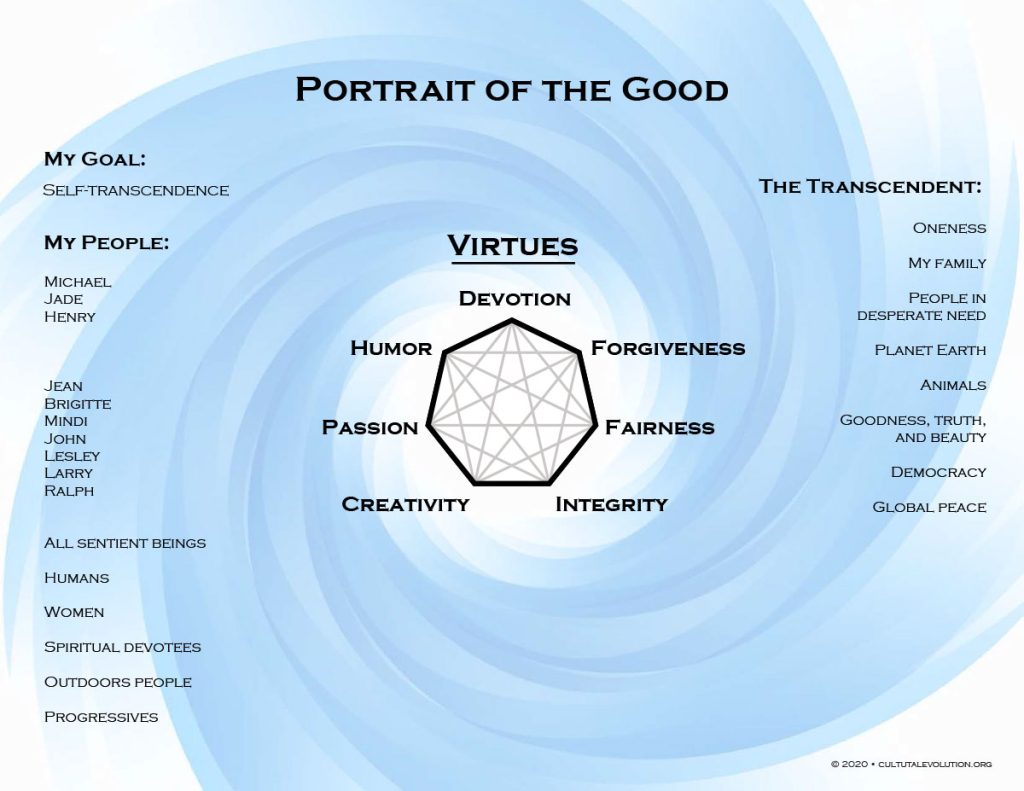

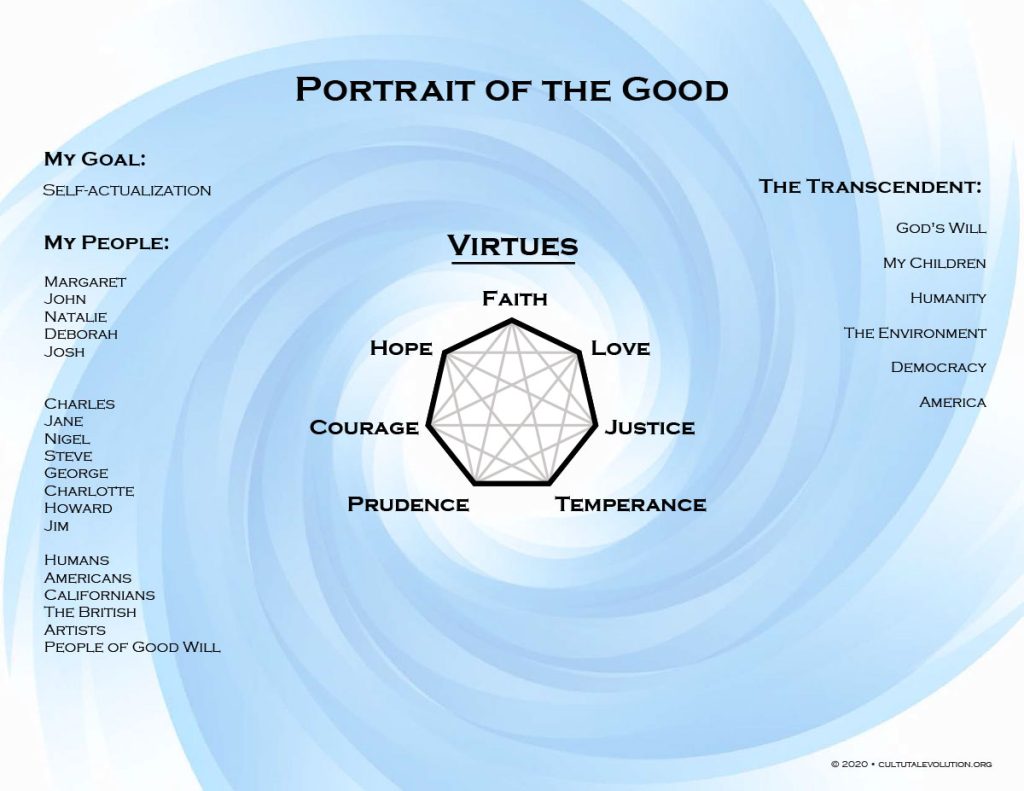

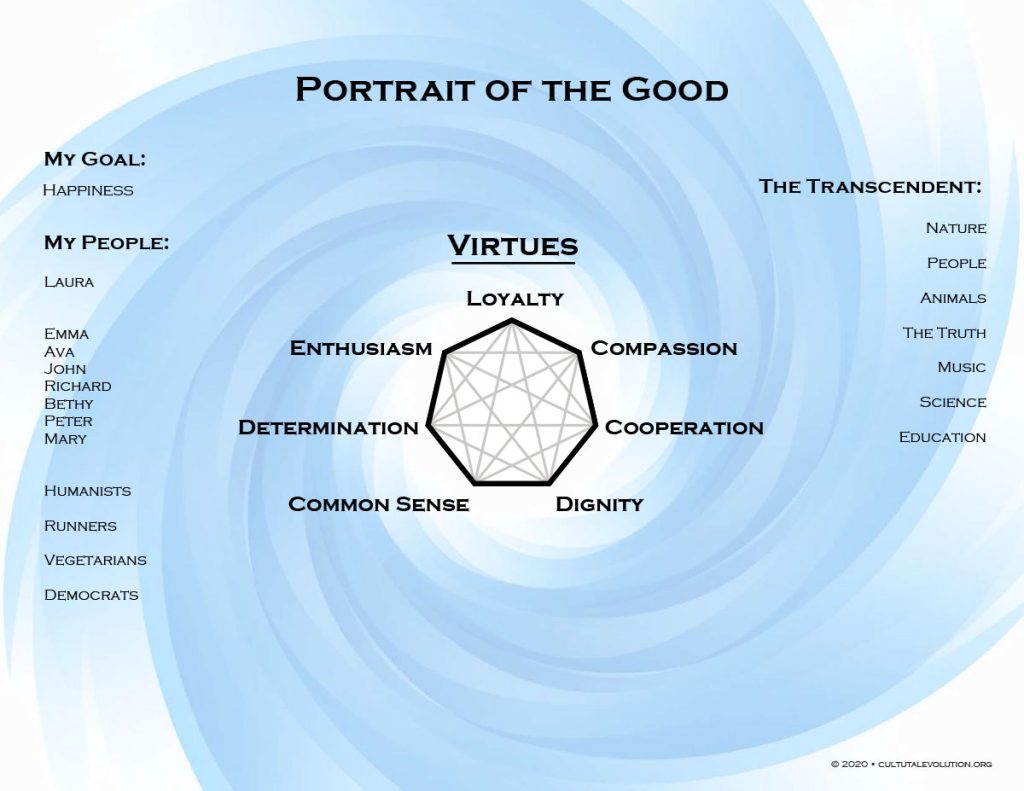

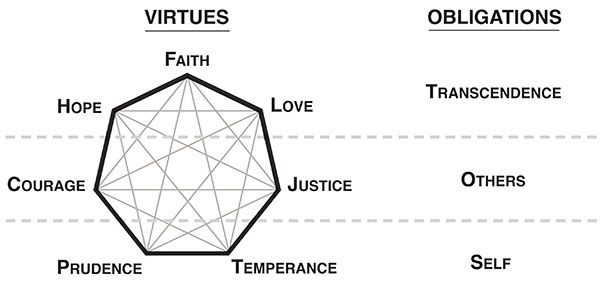

In addition to this growth in inclusivity, the developmental perspective also achieves evolution through its ability to appreciate and use a wider range of positive values than previous worldviews. That is, developmentalists can value the foundational truths, positive cultural norms, and essential works of art—the truth, goodness, and beauty—that undergird not only progressive culture, but modernist culture and traditional culture as well. Unlike progressivism, developmentalism does not roundly reject modernity and traditionalism. In short, developmentalism transcends progressivism by better including the best of what has come before.

A full-throated argument for the merits of the developmental worldview cannot be adequately made in this context, so we invite you to explore this website and read Developmental Politics, the book that fully explains our political philosophy. See also this 8 minute video clip wherein we justify our conception of “more evolved,” and this 12 minute video clip, which provides an overview of our concept of cultural evolution.

- What distinguishes developmental politics from mainstream centrism? Aren’t you just recommending a “grand compromise.”

Mainstream centrism tries to “meet in the middle” between the current versions of left and right. This entails cutting off or ignoring the “extremes” of the political spectrum. Yet this attempt to relatively balance the “two sides” inevitably situates centrism culturally within the mainstream modernist worldview. The modernist worldview, however, is now in the process of being culturally transcended by progressivism. Modernity is therefore ill-equipped to reason with progressivism or otherwise persuade it to compromise politically because progressivism rejects modernity and its pragmatic politics of give and take.

Developmental politics is not attempting to bring America’s contemporary Democratic and Republican parties together. Rather, it is working to create a new kind of political agreement space—a new home for the politically homeless—that transcends the gridlocked condition of the now largely nonexistent “center” of American politics. Developmentalists accordingly attempt to embody within their own thinking an enlarged conception of left and right, one that understands how the competing political impetuses to “fix what’s wrong” and to “preserve what’s right” are ultimately interdependent. Rather than conceiving of politics as a “fixed pie” requiring win-lose tradeoffs, developmentalists seek win-win-win solutions, as demonstrated by our evolving platform of issue positions.

From Developmental Politics: “As a result of ongoing cultural evolution from traditionalism to modernism, and now increasingly toward progressivism, contemporary American culture is being pulled apart by the competition between two seemingly incompatible communitarian moral systems—one premodern and traditional, and the other postmodern and progressive. These divergent moral systems are currently engaged in an intense political struggle for the allegiance of the modernist majority. The tug-of-war between these contending communitarian worldviews helps explain why modernists are consistently pulled toward one side or the other, and thus why centrism is not viable in our current political climate.”

- How can you expect us to accept or work with the “other side” when they deny what’s true?

America’s “post-truth” condition stems from the disintegration of our collective sense of common cause. Even in healthy and functional democracies, there will always be arguments about the true state of affairs, but responsible citizens do not believe they are “entitled to their own facts.” Therefore, to restore a greater degree of social consensus around what is true and what is false, we should start by working to restore a minimum degree of consensus about what is good.

Developmentalists are accordingly working to integrate each major worldview’s values—each faction’s notion of the good—within a transcendent and inclusive new whole. This is the focus of Developmental Politics. See also this 2 minute video clip that addresses this question.

- American politics is so corrupt, how can we make progress without first reforming our system of campaign finance?

Meaningful structural changes to our political system, such as campaign finance reform, require bipartisan cooperation, which is currently stymied by America’s culture war. Developmentalists are accordingly working upstream from the level of legislation or structural reform by focusing on cultural reconciliation and social agreement building. From our perspective, we must bring peace to the culture war (or at least a functional truce) before we will have the widespread political agreement necessary to pass complex and difficult structural reforms. See also this 4 minute video clip that addresses this question.

- Your theory of cultural evolution and worldview development seems like mere speculation. Where is the empirical evidence for your claims?

The developmental perspective is primarily founded on the political philosophy articulated in Developmental Politics. This new developmental approach is advancing a “new politics of culture” based on fresh insights into the realm of evolving values. Unlike empirical social science, political philosophy can better discern the bedrock values that lie at the heart of our national conflicts. Nevertheless, developmentalism relies on the findings of social science when and as it can.

Empirical sociological research that validates our view of cultural evolution is found in the University of Michigan’s World Values Survey, as supplemented by the related empirical research of political scientist Christian Welzel. We also rely on smaller surveys and polls such as the Hidden Tribes Report, and sociologist Paul Ray’s earlier research on the cultural creative demographic. Beyond sociological research on groups, our political philosophy is also informed by the extensive empirical research of developmental psychology, which focuses on the personal development of individuals.

- You are asking people to transcend progressivism or otherwise grow out of it. But progressivism itself is still in the process of coming of age. Shouldn’t we be working for the success of progressivism rather than trying to prematurely transcend it?

Developmental politics is working to help achieve many of progressivism’s laudable aims by better translating these goals into arguments that modernists and traditionalists can better appreciate. Applying the classical developmental model of “thesis-antithesis-synthesis” to this analysis, developmentalism can be seen as an emerging synthesis that goes beyond progressivism’s stance of antithesis toward America’s previously established culture. The emerging developmental political perspective can therefore serve as the “trim-tab” to help turn progressivism’s “rudder,” which can in turn steer America’s ship of state in the direction of political renewal and cooperation. See also this 4 minute video clip that addresses this question.

- By partially validating progressivism rather than unequivocally condemning it, developmentalists are serving as progressivism’s “useful idiots.” Progressive “cultural Marxism” threatens our civilization and must be fought against vigorously.

We can’t go backward or otherwise glue the pieces of our fragmented society back together within the old mold. So rather than fighting progressivism as in a boxing match, developmental politics is using an “aikido move” by carrying forward progressivism’s intrinsic values, even as it rejects progressivism’s anti-modernist pathologies. Developmentalists reject Marxism in practically all its forms, but we nevertheless make common cause with the best of progressivism, recognizing that progressivism is culturally ascendant for good reasons and cannot be discarded or erased.

- Why are you concerned with “progressivism’s pathologies” when right-wing extremism is really the greatest threat to American democracy?

Right-wing extremism, as exemplified by the invasion of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, is certainly a threat that concerns us. But Donald Trump’s incitement notwithstanding, very few of his supporters are actually violent lawbreakers. And unlike the extreme versions of progressivism, right-wing extremism has relatively little cultural power. Indeed, a supermajority of Americans unequivocally condemn the Capitol insurrectionists and their ilk, including far-right militias and white supremacy groups. Moreover, the FBI and the U.S. military are now devoting significant resources to suppressing these groups. So while right-wing domestic terrorism remains a serious threat, there is little chance that it will gain more power.

The extreme elements of progressivism, however, pose a more sophisticated and powerful threat to American democracy than barbaric right-wing extremists. Unlike the far right, progressivism represents both an important new layer of moral concern, and an appreciable threat to America’s democratic norms. Because most of America’s universities, as well as much of the media, have been effectively captured by progressive ideology, the illiberal pathologies of this “successor ideology” need to be countered through new forms of political activism, which developmental politics exemplifies. To preserve the minimum social solidarity necessary for a healthy democracy, progressive values must be better reconciled and integrated with the values of mainstream modernity and religious traditionalism. This is why we are focused on “transcending and including” progressivism by championing a more inclusive developmental political outlook.

- Because your political philosophy validates the “progress of Western civilization” it is essentially racist and complicit with white supremacy.

Developmental politics rejects progressive antiracism’s sweeping characterization of contemporary American society as essentially “white supremacist.” Indeed, developmental politics is generally opposed to critical theory and neo-Marxism. But we nevertheless strongly affirm that working for greater racial equality in America is necessary and important. Developmental politics also acknowledges that antiracism’s criticism is serving as a wake up call which is helping America to move beyond its complacency with the racial status quo. However, we think these critiques ultimately go too far. America has made measurable progress in ameliorating racism over the last 50 years, and this progress cannot be denied if we hope to make further progress toward greater racial equality.

Moreover, we firmly believe that Western civilization has made the world a better place overall. While there is still much work to be done to create a world that works for everyone, it must be acknowledged that most developed countries are now actively working to create more inclusive and less racist societies. Condemning contemporary Western civilization—the first civilization in history to actively oppose racism—is therefore counterproductive for the higher cause of racial equality.

- This political philosophy seems elitist.

We welcome everyone who is willing to consider the developmental perspective. And we respect disagreements and encourage constructive critiques. Because the developmental perspective attempts to be “omni-inclusive,” it cannot be accurately characterized as elitist.

Admittedly, anyone who sincerely advocates a political perspective must believe their perspective is better than the alternatives. Yet while we do contend that developmental politics is more inclusive than other political perspectives (as argued above), we certainly don’t regard ourselves as personally superior to anyone else.

Further, we believe that each of America’s major worldviews are legitimate “stakeholders” in our democracy—each set of values must have a place at the table in our governing process. See also this 14 minute video clip that addresses this question.

- Isn’t this just Ken Wilber’s philosophy?

We respect Ken Wilber. His thinking has had a significant influence on many of the Institute for Cultural Evolution’s Directors and Fellows. However, we are not “Wilberians.” Our work includes constructive critiques of Wilber’s thinking, and we depart from his theoretical conclusions on numerous points. While we do not represent or uncritically endorse Wilber’s work, we do identify with the larger body of evolutionary thinking known as “integral philosophy.” Integral philosophy is a broad philosophy of evolution that focuses primarily on the structures and larger meanings behind the evolutionary development of humanity. This philosophy of evolution begins with G.W.F. Hegel, but it is not a strictly Hegelian philosophy. Other notable philosophers who have attempted to understand the evolution of consciousness and culture, and have thus contributed to integral philosophy, include Henri Bergson, Alfred North Whitehead, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Sri Aurobindo, Jean Gebser, and Jürgen Habermas. For an intellectual history of integral philosophy see: Steve McIntosh, Integral Consciousness and the Future of Evolution (St Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2007), chapter 7, “The Founders of Integral Philosophy,” pp. 153-197.

- Isn’t this just Spiral Dynamics?

Spiral Dynamics is a “bio-psycho-social” theory of human developmental conceived by academic psychologist Clare Graves, and later popularized by Don Beck and Christopher Cowen in their 1996 book by the same title. The theory of Spiral Dynamics has had a major influence on integral philosophy, primarily through its clear identification of the progressive postmodern worldview, which it refers to as the “green” level of development. We respect Spiral Dynamics but we also recognize its shortcomings, such as its excessive linearity, its claims of empirical objectivity, and the oversimplifications which plague its proponents and practitioners. We are nevertheless indebted to the important work of Clare Graves and acknowledge his rightful place within the larger canon of integral philosophy.